A scaffold by definition is a temporary structure put in place to repair a “building or other construction.” Applying this definition to education we know that scaffolding is when we put instructional strategies in place to temporarily repair or support learning.

We, as educators, put scaffolds automatically in place to ensure our students are successful. It is important to support our learners while they are shaky and beginning to learn, practice and apply new tasks or strategies. All students can benefit from this support. We provide to them in various ways. We use guided instruction where a teacher levels instruction to a child’s level and gradually increases the level of complexity over time. This simplified lesson helps students see and understand the concept in a smaller group and allows the teacher to check and monitor progress. Teachers employ strategies such as “I do, we do, you do” to help transfer responsibility gradually to the student. Other popular ways to offer scaffolding to students are:

- Frontloading vocabulary

- Visuals and graphics

- Modeling and think aloud

- Sentence starters or word boxes

- Partner work or collaborative teams

- Graphic Organizers together as a class to organize ideas

But what happens when we do not remove this “temporary” support?

LEARNING STOPS!!

Teaching is an art and knowing when to apply and remove instructional support is crucial. We must constantly think:

- Who is the reader or student?

- What is their ability?

- What can they do?

- Are we applying tasks that are stretching this student?

- Am I providing activities and materials to help them grow and think a bit more than yesterday?

- Is the text or material we are providing continuing to challenge?

- Is the proper scaffold in place?

Constantly evaluating “Task–Text—Student” is the key to ensuring a balanced and rigorous classroom. There must be a balance between these variables to ensure continued learning. If you are providing rigorous material and tasks that stretch thinking but give too much support–you are keeping the student from learning. Rigor and learning is obtained by instilling conceptual understanding through the domains of literacy, having students matched to text and task appropriately to ensure they are stretching. Each element must work together in accordance with the instructional strategies and scaffolding the teacher is providing.

How can we lessen “learning scaffolding” AND continue with rigor?

2 IDEAS TO TRY TODAY!

Reading Task Planning

Planning the text you give students by analyzing what scaffolding the author has already provided. The elements presented should guide your planning and what scaffolding you should provide or take away.

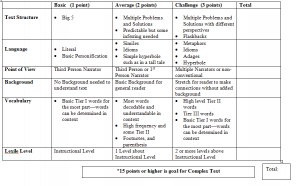

Look at this chart of a few examples of scaffolding provided by the author or in a classroom.

| Author Provided Scaffolding | Teacher provided Scaffolding |

| Title

Paragraphs Text Features Graphics Structure Perspective Patterns Repetition |

Pre teach vocabulary

Graphic Organizer Questioning Labeling Visuals Movement Prompting Think Aloud Distributed Summarizing Strategies |

If you choose to use a story out of a basal, what is provided for the reader? The author has chunked the text on pages with specific graphics designed to support the text. Vocabulary is highlighted for the reader. The author has provided the standard title which gives the main idea and it has been written in a basic fiction structure with character, setting , problem and solution.

Knowing this is your text, how much more scaffolding do your students need? Do they all need vocabulary pre-taught? Do some students need pictures removed because they rely too heavily on these? Planning is a crucial part of instruction because you are ensuring that the text and the student are matched appropriately. You want the text to be at a higher level than the student can reach without your support–this allows them to be exposed to new features, structures and vocabulary that they cannot access independently. Remember YOU are a support. You are questioning, having students talk through ideas, you are explaining–all of these allow you to control how difficult the text is for students. Taking away some of these or doing less–makes the text more difficult and providing more allows it to be easier for access.

YOU control the rigor by controlling the following elements–text, task and reader.

Plan time for students to learn in whole group, move to partners and then to independent work. Let them do the work!

After teaching a concept, it is important for students to talk through their ideas and concepts with a partner to begin to make sense of the information. Student talk is crucial to help students work through the domains of literacy (listening, speaking, reading and writing) to have conceptual understanding. More importantly, students must take time to work independently on the skill AND MAKE MISTAKES. It is not until you bring students back together to clarify and question students do they begin to make connections and to make sense of errors. The best way to take scaffolding from a student is to make them think through and do the work themselves. Give time for students to think on their own and write their own ideas into their journal or notebook. After they have generated ideas, then let them share and work together. All students should bring ideas to the table when doing group work or it is not an equal learning experience. Instead of think-pair-share, try write-pair-share-write! By changing this strategy, students are writing or drawing their ideas, getting support from a partner when discussing (deepening understanding). The sharing helps to clarify and deepen understanding further with the teacher modeling. The final write allows the student to conceptualize their ideas into written, drawings or thoughts. Labels on drawings is a great next step for younger students.

Removing instructional scaffolding is not easy because we want our students to be successful. However, we must remember that until they make mistakes–learning truly has no purpose or meaning. Let students have time to make errors and then help students fix them–that is truly TEACHING AND LEARNING WITH RIGOR.