As a new school year begins, fiction is the first reading hurdle teachers begin to tackle. Last year, in three posts about fiction text structure, I shared the following:  Without YOUR skeleton your body would have no shape and would not function. We have to help students see how an author creates the text by writing it with a structure or literary elements.

Without YOUR skeleton your body would have no shape and would not function. We have to help students see how an author creates the text by writing it with a structure or literary elements.

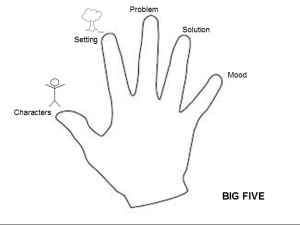

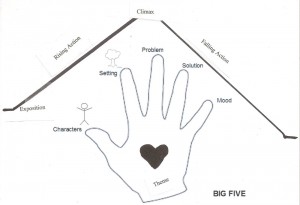

The basic elements that “hold fiction up” can be referred to as the Big 5.

It is not enough for students to simply tell you the character names, the setting, problem, etc. They must dig deeper to see how the author crafted the connection between all of these elements—that is where the depth or rigor comes in to the process. So, what does rigor look like with these elements…?

To begin, you must introduce literary elements by defining the term. An element is a “part or piece” of something and literary refers to literature a.k.a. fiction—so, literary elements are the pieces of a fictional story. But taking it to the next step is crucial. These parts or pieces work together as one unit or structure so each piece depends on the other. We need to make the connection to our students, even our youngest students, that these pieces work together to create a story. These same pieces are used repetitively so once they see the pattern—they can make predictions and have better comprehension because they know what to expect.

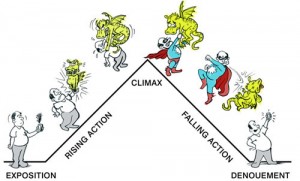

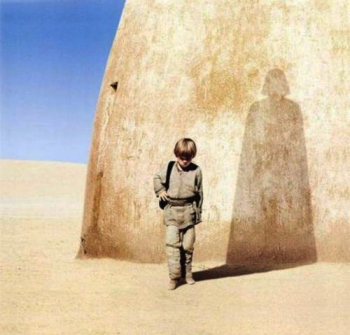

Here is how I introduce story structure to students…notice how it looks like a mountain. This is the analogy I use with students.

We must explicitly teach students as they are learning to read that text is predictable. Each story or chapter that they read is much like a mountain in that the actions HAPPEN-PEAK- and then WIND DOWN to the conclusion. The characters and setting are introduced in the beginning (Exposition) to help the reader learn important background information needed for the story. As the characters interact and the events begin to happen a problem occurs in the story. The rising action and climax is the action trying to solve the problem (often involving the pattern of three). The story begins to wind down by the problem being solved. As text becomes more complex and there is more than one plot happening—the structure changes. But, by the time students are reading at this level—their comprehension is strong enough to learn about flashback/foreshadow and other literary devices.

Here are questions and tips for the literary elements you teach that will help you deepen thinking and help students make connections between the “pieces” to the whole.

It is important that students understand that characters are normally introduced in the beginning of a story. The author takes time to describe the character so the details are important to making predictions about the character’s purpose in the story. Really focus students on actions, dialogue, thoughts, feelings because it is the way the author has to “show you” inside a character. You can equate this to a movie—an author has to tell you in words what you normally would observe. Show a movie trailer and ask the students to write down words to describe the character as they watch. Make sure you ask them to substantiate their thinking with evidence from the movie. Let them turn and talk after and brainstorm with a peer. As a class discuss character traits and their evidence. Have students write phrases an author might use to describe the character to see the connection between an action and trait. Be sure to ask students questions to help them look for connections between characters (relationships), motivations and inclinations which can lead them to making better inferences and conclusions.

Character

- What does the character look like? Do any of the physical traits make you judge the character different?

- How does the character act? Do their actions make you like or dislike them? Why?

- Are the characters similar or different? How? (Good vs. Evil?)

- How does the character feel about ________________?

- Is one character more important than another? Why? How do you know? (primary and supporting characters)

- What is the mood of the character? What caused the mood? (significant event)

- What character traits do they posses? What dialogue, actions, thoughts or feelings help you determine your opinion?

- How would the character act in a different situation? How do you know?

- How does the character feel about ____________? Why? What can we infer from the character from this?

- What is the mood of the character? What caused the mood? Did the mood change? How is the mood of ____________different from ____________________? What can we infer about these characters? Why did the author decide to make their feelings different?

Getting a quick answer for setting such as outside, inside, a forest, etc. is normal but really makes students dig to see that descriptions of the setting help to let you know if suspense is building or if a change in a character may be ready to happen. Read sections of description and have students sketch what they think the author described. Have the students label their descriptions with key words from the text. This activity builds vocabulary, helps build connections and more importantly helps you to see if students are able to visualize as they read.

Setting

- Are you surprised by the setting of the story or does it seem appropriate? Explain

- Are the characters comfortable in this setting? Is one more comfortable than another? Why?

- Is the setting described by the author? What details are given that are most vivid? Why?

- Does the setting help the reader create a mood in their mind? If so, what mood? What words make you feel this way?

- What word best describes the setting? Why? What was the most vivid adjective used by the author to describe the setting? Why?

- Read an excerpt aloud. Have students sketch the setting or character. Have them label with details from the text.

- Would the characters have to change if the setting was different? Explain

When Setting Changes

- How did the characters change or react to the new setting?

- What caused the new setting? (significant event)

- Did the setting cause a mood change in a character? more than one character? different moods? Why?

- How is the setting different? How will if affect the characters differently?

Events directly correlate with the character’s mood and actions. When students notice a mood—have them tell you what event is happening because this is significant. Stories have a main problem and students need to know that as they read more difficult text, they will encounter plots with several problems throughout the story. Learning to note the problems, which they affect and if they are a primary or secondary problem is crucial for students to understand more complex text. Really examining events helps students understand why we learn cause and effect and how the pieces of a story begin to fit together. Out of sequence the story does not make sense.

Problem

- What is the problem?

- Who caused the problem? Why?

- Is the event a problem for all characters? Explain why it might be different for different characters.

- Why is this a problem for ________________ and not for _______________? What does this tell us about these characters?

- How will the problem affect _____________________? Explain

- Did the problem cause any other problems? Explain?

- Is this a primary problem or secondary? How do you know?

- Does the problem cause a character to change their mood or belief in something?

To solve a problem, an author will often go through a series of attempts (pattern of three). Helping students see that these attempts are the author’s way of keeping you interested (suspense). Solutions are normally found close to the end and are a sign that the story or chapter is wrapping up.

Solution

- Was the problem completely solved?

- Were all characters pleased with the solution? Explain why or why not.

- Are there any effects from the solution?

- Does the solution cause another problem? Explain

- How does the solution affect each character?

- Can you make a prediction about what will happen next?

- How does the solution teach a lesson? Do all characters learn a lesson?

The Common Core Reading Standards are already in a scaffolding pattern as they are written.

The first 3 standards are classified as Key Ideas and Details because they are examining basic pieces or elements of a text.

- RL.1 and RL.2 focus on general understanding of the text including the basic Who, What, When and Where questions. L.2 begins to have students see how pieces fit together to determine a theme or main idea.

- RL.3 begins to examine a character. Looking deeper at text, illustrations and other characters to determine more about a character. (CHARACTERIZATION: Direct and Indirect)

Standards 4-6 go deeper into the text and require rereading and close reading to examine text in a different way. These are classified as Craft and Structure because students are digging into the literary elements and looking for relationships.

- RL.4 demands students to dig deeper into the text at words and phrases. What are the meanings? What do they tell us about a character, setting, mood or event?

- RL.5 begins in K-2 as understanding the structure of fiction is different from non-fiction and basic sequence of events. As students gain understanding and move to more complex text, they are asked to examine how events fit together and how one section, event, or chapter may build on the next and work in an interrelated fashion.

- RL.6 is the point of view standard which requires students to first distinguish their own opinion from the author and the story. Once they master this skill they can begin to see how multiple characters see ideas, events, and dialogue differently and how it affects events, characters and the problem/solution.

The final three standards are the most complex because they are the Integration of Knowledge and Ideas standards. These require students to use multiple ideas together, find connections and make comparisons and contrasts.

- RL.7 requires students to examine illustrations and how they contribute to the text. This moves into the tone and how the author’s phrases, word choices and descriptions can directly affect characterization, settings, events and plot development.

- RL.8 is not applicable to fiction

- RL.9 is the standard that has students compare and contrast. Not just comparing an entire story to story but looking at different elements and examining them across texts or excerpts.

As you begin planning this year, think about how you will use a text and move students from one standard to another within that text. It is by rereading and reexamining the text in different ways that you move students to the depth of the standard. Simply asking questions is not enough but moving students in a pattern that requires them to rethink, reread and formulate new ideas will lead to better comprehension of the text. I challenge you to reread the same text for several days and continue to deepen the students understanding with a higher level of questioning.

Happy Fictional Text Planning! Remember I am available if you need help!

Earlier Posts on Fiction Text Structure:

Fiction Text Structure: https://thiskelly.edublogs.org/2015/10/10/fiction-text/

Fiction Text Structure for K-2 Students: https://thiskelly.edublogs.org/2015/10/16/fiction-text-structure-k-2-or-remediation-students/

3-5 Fiction Text Structure: https://thiskelly.edublogs.org/2015/10/17/3-5-fiction-text-structure/

Understanding and seeing foreshadow will help students pick up on subtle hints that something is going to happen or a future event. This help students make predictions AND to learn to find small details and make connections and inferences. Flashback is a technique used to stop current events and have a reader go back in time to build background or see a past event. This is tough for students who are not proficient readers because they do not realize that the event is not currently happening. Teaching this to students helps them learn how to sequence events. It also helps students make connections between more than one character, events and settings.

Understanding and seeing foreshadow will help students pick up on subtle hints that something is going to happen or a future event. This help students make predictions AND to learn to find small details and make connections and inferences. Flashback is a technique used to stop current events and have a reader go back in time to build background or see a past event. This is tough for students who are not proficient readers because they do not realize that the event is not currently happening. Teaching this to students helps them learn how to sequence events. It also helps students make connections between more than one character, events and settings.