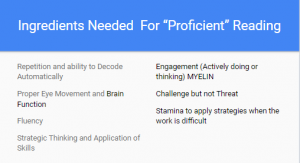

In a workshop last year for silent fluency, I showed this slide.

Rand Reading Group (Snow 2002) reinforced my slide by stating the following, “for students to successfully “negotiate textual meaning the reader must bring at least the following to the act of reading: cognitive capabilities, motivation, linguistic knowledge and experiences.”

What Rand Reading Group included that I did not was linguistic knowledge and experiences. Linguistics refers to the structure of language. Syntax is part of linguistics because it is the art of combining words together to make sentences, the proper word order and punctuation which helps to build the structure of our language. (Grammar)

I bring this up because syntax is almost subconscious at early ages, being created through speaking and listening. As children speak and listen, they are learning how words are combined to create sentences and questions. As they encounter language through listening and modeling, the sentences become more complex. You have heard a small child say, “see dog.” The adult or other child will say, “Yes, you see a dog.” As time progresses the child begins to clarify and say, “I see a dog.”

The complexity of language and “syntax” increases each year as the child gets older and has different experiences. Sentences become more complex and vocabulary more abstract. According to J.S. Chall (1983), by the 4th grade the grade level text structure students are exposed to begins to exceed conversational language.” This is a HUGE discovery for me because we all know about the “4th grade slump,” this seems to help to explain that gap. The rigor or complexity in the language of the text is higher than the students are use to putting in order or comfortably recognizing.

Syntax affects fluency and comprehension because it is the student’s ability to chunk sentences into “syntactic chunks” that help with intonation, stress and pause as they read.

We, as teachers, do not really think about syntax but it plays a large role in reading fluency and comprehension. A few facts about syntax that teachers NEED to know.

- Syntax awareness at 1st grade predicts word recognition at 2nd (Tunmer, 1989)

- Poor readers have difficulty detecting and correcting syntactic errors. (Bentin, Deutsch, and Liberman, 1990)

- Lower levels of syntax awareness usually correspond with lower fluency and comprehension performance.

- If you increase syntax awareness than you can increase reading ability in both fluency and comprehension.

So, bottom line, what are the implications for our students and classrooms? How do we build syntax awareness for our students?

Speaking in complete sentences! By encouraging students to put all answers and thoughts in complete sentences, you are helping them to practice the art of syntax (applying word order). Help students to extend sentences and to make more complex sentences.

Create more complex sentences than they are used to speaking and reading and have students put them together on sentence strips. If you have students who are still speaking in simple sentences, then give them a compound sentence on a sentence strip. Ask them to put it together. They will want to make two sentences but will see the conjunction holds it together. For older students, give them sentences with phrases, clauses and unusual punctuation By exposing them to these types of sentences, you are instructing them on language that is above the level they normally speak in conversation and will be reading as they move to more difficult text.

Focus on chunks. The brain has the ability to process four words at a time so thinking about sentences in chunks helps the brain process information and the language easier. For example: The little red hen and the yellow bunny sat around the campfire. When students are learning to read this and think about how to read—they should see the word “and” which means it is a conjunction holding subjects together so on either side is a chunk. The verb usually starts another chunk (predicate). This helps students with fluency and not reading one single word at a time. Modeling how to chunk a sentence and explicitly teaching sentence parts helps students to better determine how to process as they read.

Use all the domains of literacy to build conceptual understanding. To truly understand any concept, a child or adult must work the idea through all domains of literacy. Students must first hear the information (listening) through modeling, think aloud and direct instruction. Students next should speak the information through student to student interaction. The step of speaking allows students to process the information and to own it. They are putting together their own sentences to make sense of the knowledge (summarizing). The next step, now that they have proper background, they can begin reading on the topic. The final step to show true conceptual understanding is when a child can take the information, rearrange, process and make the information their own in writing. This shows that they have a deep understanding and strong command of the information.

Revisiting the above quote from Rand Reading Group (Snow 2002), “for students to successfully “negotiate textual meaning the reader must bring at least the following to the act of reading: cognitive capabilities, motivation, linguistic knowledge and experiences.” The teaching of syntax directly through grammar and punctuation instruction paired with speaking and listening helps students have the linguistic knowledge and experiences to effectively decode text and read with prosody.

Motivation will be another Blog!

Resources considered and read for this Blog:

Article entitled: 8 Common Mistakes in Modern Language Instruction by claraalert on guestblogger which was accessed on 9/12/2017

Article entitled: The Role of Early Oral Language in Literacy Development by Timothy Shanahan and Christopher Lonigan which was accessed 9/10/17

PPT archived on Internet by Michael Sullivan on Significance of Syntax (I am unsure of ownership of this but found this in the title it was saved in.)

Chall, J.S. (1983) Stages of reading development. New York: Harcourt Brace which was cited in the PPT discussed below.