Education is a world of acronyms and vocabulary that do not seem to fit into the “real world.” In the spring, in a blog entitled, “Accommodations and Modifications and Educational Lingo—Oh My!” I tried to clarify terms such as accommodation, intervention, progress monitoring and remediation to ensure we use the right word in the right context.

After many data studies and conversations, we as a school, have decided that we need to “up our rigor.” We use words like rigor, conceptual understanding, and complexity—what in the world? This blog will seek to clarify these terms to help you understand what your instructional coach is TRYING to say and wanting you to do!

The words Rigor and Complexity are the main buzz words at our school right now—but what does this mean?

Rigor is an overarching term that refers to the teacher’s ability to create a balance between the reader, task and text. I like to think of the dangling carrot—because this demonstrates the engagement that is created when the reader is matched appropriately (just barely out of reach) to the text and the task.  Rigor requires constant adjustment by the teacher between scaffolding instruction and change in materials and activities. When a student attains, the teacher should constantly “move the carrot” forward to encourage thinking and learning. “Moving the carrot” or rigor requires three components working together which are:

Rigor requires constant adjustment by the teacher between scaffolding instruction and change in materials and activities. When a student attains, the teacher should constantly “move the carrot” forward to encourage thinking and learning. “Moving the carrot” or rigor requires three components working together which are:

1) Conceptual Understanding through the Domains of Literacy

2) Procedural Fluency

3) Real World Application

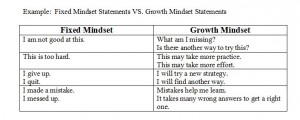

More crazy terms—right?? Conceptual understanding simply means that a student can speak, read and write about a concept. If a child can understand a concept to the point that they can share their thoughts, manipulate the thoughts into another format or put them in writing—they have conceptual understanding of the topic or subject. Procedural fluency simply refers to the application of foundational skills necessary for the student to show conceptual understanding. They can apply foundational skills effortlessly and automatically. Finally, real world application refers to taking the new knowledge or information and using it in a meaningful way that requires applying, synthesizing, creating and evaluating. Real world application does NOT mean that it has to be how they would use it in the real world. It means that it needs to be relevant to the child. The three components of rigor work together to ensure that you are increasing expectations for students and ensuring that you are “moving the carrot” forward for students to continue learning.

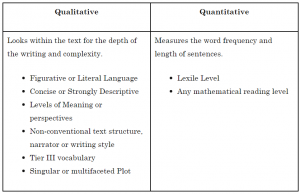

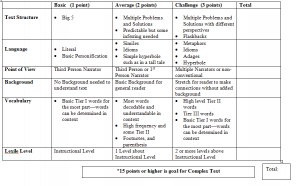

Complexity is more specifically related to text or a task. To examine whether something is complex, you must look at quantitative and qualitative measures.

A text or activity is complex when it balances both qualitative and quantitative measures. If you use a complex text, you may balance it with scaffolding and text features. If the text is less complex, then take away the scaffolding to require students to dig deeper into the text independently. Don’t fall into the trap of just giving a higher lexile text to students because the lexile is only measuring words, phrases, syllables, etc. A lexile level does not take into account the meaning and author’s craft. Remember that The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck is lexiled at 680L which is a second/third grade reading band. Really? Be careful when choosing text and remember to KNOW it- because the qualities it possesses can make it complex regardless of the lexile or vice versa.

With an increase in rigor and complexity, you hear the words scaffolding, text dependent questions and higher order questioning. These terms refer to instructional practices utilized by teachers to ensure that you are extending or supporting learning for your students.

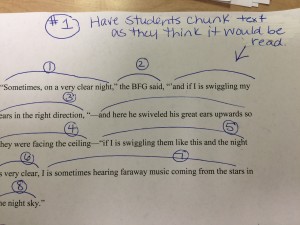

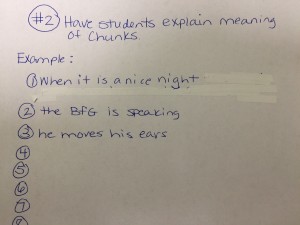

Scaffolding is a word that encompasses all the ways teachers support a learner while they interact with text or content. This can take the form of the materials you provide such as graphic organizers and text feature support. It can take form in the instructional strategies you use such as turn and talk to support thinking or Socratic questioning to extend ideas.

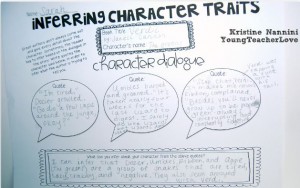

One important element of scaffolding is questioning. Text Dependent Questions are questions that are tied directly to the text and require the student to find evidence to support their answers WITHIN THE TEXT. Higher order questioning is similar but usually refers to using the levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy or Marzano’s Thinking Levels. Both of these taxonomies require thinking to develop from the concrete—right there questions to the more abstract. Both types of questioning have a place and importance in daily instruction. (See resources below for more information on types of questioning)

As we progress through the year, on the blog, I will periodically review educational “lingo” we are using that may be confusing or used inappropriately. Please remember to ask if you are unsure! If you do not know, others are probably unsure as well.

Resources:

Bloom’s Taxonomy from Curriculet

http://blog.curriculet.com/38-question-starters-based-blooms-taxonomy/

Marzano Question Stems

http://www.hwdsb.on.ca/rosedale/files/2014/12/QUESTIONS-TO-ASK-YOUR-CHILD-AFTER-THEY-READ.pdf